Glycoalkaloids in Potatoes

Potato sprouts do contain potentially harmful concentrations of glycoalkaloids, compounds that can be toxic (causing solanine toxicity if you want to be specific). But sprouted potatoes don't have to be junk: the potatoes themselves are probably still safe to eat, as long as you cut off small growths and green spots -- unless the potatoes are also very soft or wilted, which is a bad sign. Never eat bitter potatoes!

In a 2006 paper published in the Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry, USDA research chemist Mendel Friedman explained, "Glycoalkaloids are produced in all parts of the potato plant, including leaves, roots, tubers and buds." They are also found in other fruits and vegetables of the nightshade family, including tomatoes, bell peppers, and eggplants. The Centre for Food Safety has studied the content of two natural toxins, glycoalkaloids and cyanogenic glycosides, in plants commonly consumed by Hong Kong people. The results of the study showed that different amounts of glycoalkaloids were also detected in fresh potato samples of different varieties on the market. , the content ranges from 26 to 88 mg per kilogram (average 56 mg per kilogram), the content is normal, that is, the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization / World Health Organization Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives believes that eating every day will not be a problem. The content of glycoalkaloids in potato sprouts is relatively high.

In the past, there have been cases of acute poisoning caused by ingesting a large amount of glycoalkaloids (such as solanine (also known as solanine)) from eating potatoes. However, all potato tubers contain small amounts of glycoalkaloids, and the potato peel and metabolic activity are strong The content of some parts is higher, such as bud eye. Glycoalkaloids are higher in green potatoes, and can be quite high in the sprouts; potatoes with high eggplant salty content have a bitter taste after cooking and can cause a burning sensation in the throat after eating. Generally, the content of glycoalkaloids in edible plants will not cause poisoning. However, ingestion of large amounts of glycoalkaloids can produce toxic effects. When the potato has just sprouted and has not grown much, you can dig out a piece of bud and bud eye, and the rest can still be eaten, because at this time the toxin is still concentrated in the bud eye and the nearby parts, and the toxin has not yet expanded.

Acute toxicity

When ingested in large enough doses, glycoalkaloids can have some pretty nasty effects; symptoms of solanine poisoning include abdominal pain, stomach cramps, nausea, and vomiting. The levels of these toxic compounds in the roots (i.e. potatoes) themselves are usually too low to have any ill effects. But "bean sprouts contain a higher amount than leaves or tubers", so it's best to avoid them.

Friedman mentions that "light, heat, or mechanical damage can stimulate glycoalkaloid synthesis," which is why it's a good idea to store potatoes in a cool, dark place. Additionally, light triggers the formation of chlorophyll, which itself is harmless. But it will cause the potatoes to turn green in the same places where the toxin is most likely, as a visual cue for the parts you should avoid.

Foods containing cyanogenic glycosides (such as cassava and sorghum) are staple foods in some parts of the world, and other edible plants containing cyanogenic glycosides include bamboo shoots, flax seeds, seeds of stone fruits (such as apricots and peaches), peas and beans (such as lima). bean) seeds, and soybean shells. Other foods that may contain cyanogenic glycosides include some food ingredients used for flavoring, such as almond flour.

How to prevent potatoes from sprouting easily

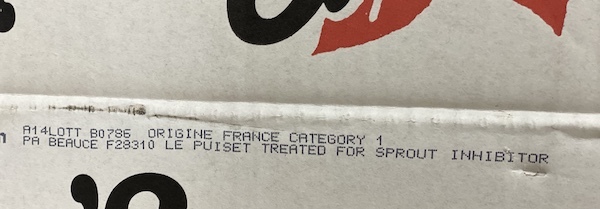

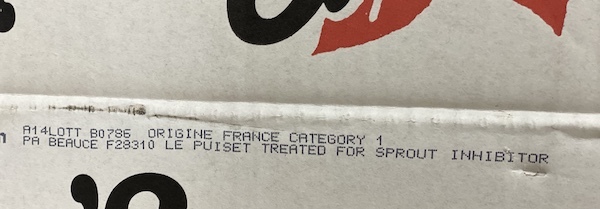

On the market, general potato suppliers will treat with a special germination inhibitor (sprout Inhibitor, e.g. MH), and naturally it will not be easy to grow buds.

Every spring and summer, when the weather is humid and the weather warms up, potatoes are more likely to germinate. However, avoid buying potatoes that have been stored at low temperature by suppliers. Put the potatoes in the refrigerator and leave them at room temperature. If they are affected by sunlight, it will stimulate the “rejuvenation memory” of the potatoes to stimulate their growth. To prevent the potatoes from turning green and sprouting and producing glycoalkaloids, the potatoes should be stored in a cool, dry place. If the potatoes are kept at room temperature, they can be placed with apples, and the ethylene gas emitted by the apples 🍎 can effectively slow down the germination of the potatoes. , And potato should also be placed in a cool and dark place, avoid direct sunlight, avoid chlorophyll growth, and affect potato turns green.

Bottom line

Cut off the sprouts and any green specks before cooking, and the leftover potatoes should be safe to eat. However, if you do notice an unusually bitter taste in the potatoes, this may be a sign of increased glycoalkaloids in the roots and should not be eaten. If it's wrinkled and soft, throw it away too.

References: